If you’re not primarily working with NLP you may not have been paying attention to topic modeling and word embeddings. In this post I intend to convince you that you should.

Topic models

Topic models are a set of models in NLP that discover common themes in a collection of documents. You give it a list of texts and it comes up with a bunch of topics and maps every document to a topic or a mixture of topics. Here you can see a visualization of a topic model applied to wikipedia articles. As you can see, it picks up similar kinds of themes in the texts that a human being would notice. Take topic 5 for instance. Its top relevant words are “war”, “force”, “army”, “attack”, “military” and top articles: “Second Boer War”, “Erwin Rommel”, “Axis powers”, “Vietnam war”. Pretty neat. Most topic models (like the most popular LDA produce a vector of numbers for every text - the distribution of topics and a similar vector for every word - the affinity of the word to every topic.

Word (and document) embeddings

Word embeddings are related to topic models but instead of mapping a text to a mixture of topics they learn to map words to real valued fixed-size vectors. The mapping is designed to preserve the semantic structure so that the distance between vectors corresponds to distance in meaning of words. An additional property of these embeddings (probably unintended) is that you can do a sort of algebra on words - like this:

- an examples taken from the most famous word embedding algorithm -word2vec. How cool is that? If you want to play with the vectors yourself and discover new fun analogies ($Bush - Iraq + Vietnam \approx Nixon$ !!!) you can download pretrained vectors from word2vec or GloVe.

Why you should care

Unsupervised algorithms learning about analogies between real-world entities is pretty cool but it obscures the wider applicability of these algorithms. The topic modeling and embedding algorithms were invented in the context of NLP but most of them (including LDA and wor2vec) don’t have any inherent knowledge about natural languages and can be applied just as well to sequences of items from a discrete set of any kind. This is huge. Sequences (or sets) of items are notoriously hard to work with. Most popular ML algorithms expect fixed-size vectors as inputs. If your inputs are sequences you can either:

- do one-hot encoding and then use any old ML algo you want (like a random forest). Unfortunately one-hot discards all information about the order of items. More importantly, as the size of the vocabulary grows beyond thousands (which is still tiny as far as vocabularies go) your random forest will take forever to train and overfit.

- use naive bayes. NB works surprisingly well but only for classification and only when the problem is - well, naive. It also utilizes the item order information to a very limited extent via n-grams.

- use a recurrent neural network This can actually be very effective in some cases but I don’t think it would work well with a vocabulary size in the thousands. Even the character-level language models take days to train properly on a GPU (but what incredible results it produces!). I believe NNs of all kinds will get better and easier to use but as of now this is not a practical solution to our problem at all.

This is where word embeddings come in. Just run word2vec on your sequences of items and you’ll get a reasonably-dimensional representation of every item. You can then take the mean of all vectors in a sequence to get a representation of sequences. Or run doc2vec and you’ll get a vector for each sequence directly. Or if you need them clustered - run LDA. LDA’s word-topic coefficients can also be used as word embedding but they don’t do nearly as good of a job at it as word2vec. Same goes for LDA’s text-topic coefficients as a document to vector mapping.

This is it. This is what topic modeling buys you. It’s a generic clustering and feature extraction technique that works on sequences (or sets) of items from a discrete vocabulary. Does it actually work in practice? I don’t know of a lot of examples of people using it but I know a few.

Page jumps

As I have already described in my mini-guide to data science interviews (question “Predicting page jumps”) it can be used to model users jumping between pages of a web application. Here a page plays the role of a word and a user journey is a sentence. You can (and from what I understood from the interview - they [the company I interviewed with] do) use topic modeling to segment users based on their journeys and extract features for them to predict page jumps.

Ad clicks

In a similar vein, topic modeling has been used as a feature extraction technique in the prediction of ad clicks. The paper concentrates on the authors’ special brand of topic modeling but the idea is simple and can be used with any topic model for example LDA. They treat hosts (the websites with banners on them) as words and users who visit the websites as documents. Let’s say John visits youtube then google then wikipedia then youtube again then tmz then guardian. This gives us a sequence [“youtube”, “google”, “wikipedia”, “youtube”, “tmz”, “guardian”]. Topic modeling is applied to the set of all users and the result is a set of topics (“media”, “business” and “drive” in the paper) and a decomposition of every user into those topics. So for our John we should expect something like {media: 0.8, business: 0.2, drive: 0}. This is interesting in itself and constitutes a great feature vector that you can feed into a regression predicting clicks - which is exactly what the authors did.

DeepWalk

Feature extraction from graphs is even harder than for sequences. Say you want to classify youtube videos. You have a labeled training set and a set of features for every video. But you also know that some videos link to other videos - forming a graph. Information about the position of the video in this graph is bound to be useful for classifiaction (think “oh, I’m in that weird part of youtube again”) but how do you use it. Authors of the DeepWalk paper compared several approaches and the best turned out to be a trick involving word2vec that they invented. This time the role of a word is played by a node in the graph (a youtube video). What plays the role of a sentence? For that a collection of short random walks on the graph is constructed - starting at every node of the graph. Think about what happens when a youtube video ends and another one starts playing, and then another one and another. Do this a few times for every video on youtube and you have a corpus of texts. Authors of the paper applied word2vec to those sequences to get vector embeddings for videos and then used these vectors as features in classification. It worked better then all other approaches - even ones that use global features of the graph. Awesome.

Update July 2016

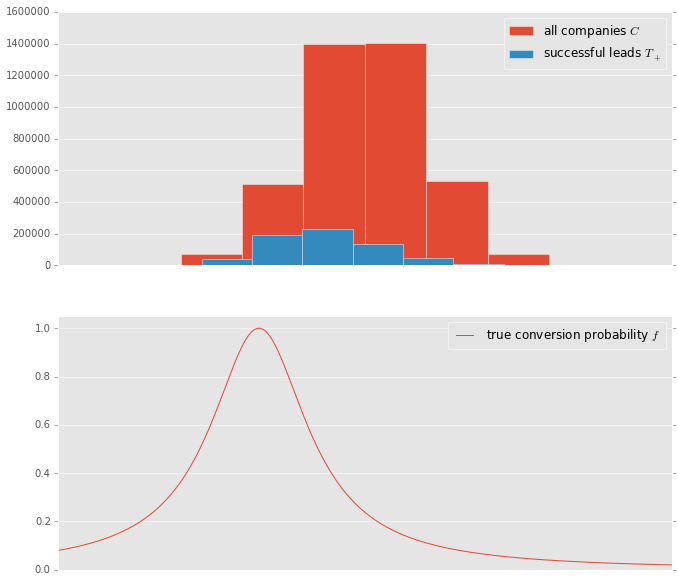

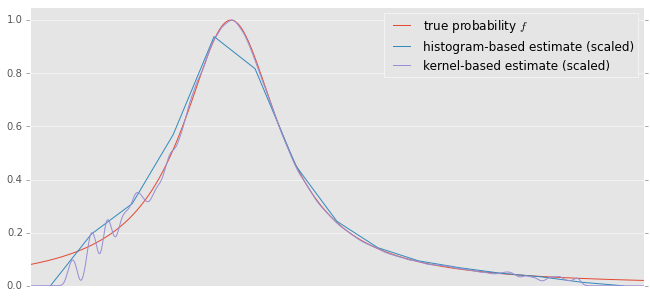

I have tried this very algorithm on the graph of UK and Irish companies, here are the results

Frequent itemsets / collaborative filtering

Association rule learning is a popular task in the context of retail. If a customer bought butter and bread, what other item are they likely to buy? The usual approach is to count instances of people buying {bread, butter, X} and divide that number by the count of people buying {bread, butter} - this estimates the probability of buying X. Then you can find the X that maximizes the probability and do something with it (suggest it to the user as they are about to checkout perhaps). This is a bit crude, not very robust and it doesn’t provide any insight, just the prediction. What you can do instead is to run (you guessed it) topic modeling with items playing the role of words and baskets playing the role of sentences. Word2vec will give you vector representations of both items and baskets which will allow you to use more sophisticated algorithms for predicting the next item. You will also get a segmentation of all users and all items for free. To understand why this is superior consider this: topic modeling will easily pick up on the cluster of vegetarian buyers and then the model will know not to recommend the buyer pork chops even if they bought three other items that usually go with bacon - this is something frequent itemset algorithms are incapable of. When a new type of soy-based pork substitute appears on the shelves, the algorithm will also take much less time to figure out that it belongs to the vegetarian cluster and is analogous to meat. I don’t actually know if anyone in retail is doing topic modeling on baskets but if they don’t, they should. I’ll do it myself if I can find a free dataset with retail baskets.

Update July 2016

Called it. People are totally doing that now here and here. I don’t know why in the above text I fixated on frequent itemsets - which is just a specific, outdated way of doing collaborative filtering.

If you know of any other cool applications of topic modeling to non-NLP problems let me know.

If you want to play with topic models yourself I wholehartedly recommend gensim. I tried also MLLib but its word2vec implementation required 3 times as much RAM (for each of 10 cores I used) and still was about ten times slower than gensim.